Panpsychosis: The Finitude of All Things

Why everything is not conscious, qualia formalisms fail, and even hell must end.

To make any declarations about reality, we must first agree upon a definition of “reality”. As I note in Epistemic Entropy, our models serve as a map for some experienced territory, where the segmentation of phenomenal patterns between map and territory is determined dynamically according to pragmatic utility, in line with Bertrand Russell’s neutral monism. The territory can never be fully captured by any model, because it is necessarily more chaotic and dense—what Lacan calls the traumatic Real. Generally, when we speak about reality or truth, we refer to a high degree of map-territory correspondence. But we also occasionally speak of that which is not accessible, a reality outside of what we can experience—Kantian noumena. This is decidedly distinct from the Real in that it is metaphysical—physics about physics, or roughly, speculations as to what rules cause our accessible physics to emerge.

In Epistemic Entropy, I elaborate that a rejection of Cartesian dualism—the presence of a concrete distinction between mind and body, map and territory—does not necessitate a total collapse of distinction. Distinction trivially exists in a neutral monistic sense: we clearly split the world functionally into mind and body. Neutral monism does not posit that the universe is made of any “fundamental quality”: any monism that is not neutral is spiritually Cartesian in that it assumes the conclusion that everything is fundamentally of one certain observer-independent non-neutral quality or another. In this sense, neutral monism is something of an anti-metaphysics: we cannot say anything about the universe except that it exists, and that we consciously segment it into parts. With this out of the way, we may now begin to speak of reality.

Solipsism

“Solipsism” is a deeply confused language game. If by solipsism we mean that we can only access our own subjectivity, then it is trivially true. If by “only my mind exists” we mean “I can only access my own mind”, then it is trivially true. But there are clearly unfathomably rich mechanisms we cannot access that generate our physics. The Standard Model is just too intersubjectively consistent across trillions of observations: we can make predictions about orbits of bodies we cannot observe; quantum entanglement reliably generates non-local correlations; physical states of the brain consistently correlate with conscious states. Meta-rationally, we must conclude that there is some mechanism that is forcing all of these interactions to follow a consistent set of rules—but evidently, we cannot subjectively access whatever this is.

Even so, once we concede that there is obviously something outside of awareness, we might still defend a form of “solipsism” by suggesting that these mechanisms only generate our consciousness. That is, there is some mechanism that keeps track of all hypothetical far-away phenomena everywhere in the world, maintains the correlation between our consciousness and the physical state of the brain, magically synchronises the physical brain states of other people with their behaviours, etc. Of course, this is a metaphysical absurdity—what would simulate the simulator, and according to what laws? Solipsism is fundamentally an ontological narcissism: the idea that there is an absurdly complicated Rube Goldberg machine that generates the illusion of spatiotemporal coherence across trillions of phenomena—specifically only for a single consciousness. It is patently more parsimonious to suggest that there is a noumenal reality in which there are other subjects—or in other words, practically, this is how our world works. Of course, we can’t strictly falsify solipsism, but Popperian falsificationism is only useful when applied meta-rationally according to context; as an autistic dogma, it collapses into total impracticality. As Žižek notes in Less Than Nothing, meta-rationality is a matter of faith:

In order for me to be practically active, engaged in the world, I have to accept myself as a being “in the world,” caught in a situation, interacting with real objects which resist me and which I try to transform. Furthermore, in order to act as a free moral subject, I have to accept the independent existence of other subjects like me, as well as the existence of a higher spiritual order in which I participate and which is independent of natural determinism. To accept all this is not a matter of knowledge—it can only be a matter of faith. Fichte’s point is thus that the existence of external reality (of which I myself am a part) is not a matter of theoretical proofs, but a practical necessity, a necessary presupposition of myself as an agent intervening in reality, interacting with it.

The irony is that Fichte here comes uncannily close to Nikolai Bukharin, a die-hard dialectical materialist who, in his Philosophical Arabesques (one of the most tragic works in the entire history of philosophy—a manuscript written in 1937, when he was in the Lubyanka prison, awaiting execution), tries to bring together for the last time his entire life-experience into a consistent philosophical edifice. The first and crucial choice he confronts is that between the materialist assertion of the reality of the external world and what he calls the “intrigues of solipsism.” Once this key battle is won, once the life-asserting reliance on the real world liberates us from the damp prison-house of our fantasies, we can breathe freely, simply going on to draw all the consequences from this first key result.

Panpsychism

And thus, we can begin to tackle notions of panpsychism—the idea that the fundamental nature of reality is conscious. Bernardo Kastrup’s analytical idealism, David Pearce’s non-materialist physicalism, open individualism, and other formulations of substance monism all essentially derive from this same idea. Most panpsychist-adjacent frameworks justify themselves as being a necessary solution to the so-called hard problem of consciousness, as coined by David Chalmers, which is essentially the idea that consciousness is uniquely inexplicable. In The Idea of the World, Kastrup argues that since all other macro-scale phenomena can be reduced to their constituent parts, consciousness poses a unique problem, and must therefore be ontologically primitive. However, this is obviously absurd. A salient example of this is mass, which according to our best models arises due to the Higgs mechanism. But we have no idea how or why this mechanism occurs, and moreover, due to computational irreducibility, we effectively never can. We might as well suggest a “hard problem of mass”: most phenomena in the universe are inexplicable, or cannot logically be broken down into constitutive phenomena without significant loss of information, as demonstrated by the concepts of emergence and chaos theory. Furthermore, “macro-scale” is relative: there is no reason to believe that there is any fundamental structure in a bottom-up sense. The smallest volumes may theoretically be reducible to even more fundamental “rulesets”, which may be reducible even further, and so on. False vacuum decay suggests that even the known laws of physics are temporary, emergent phenomena.

Furthermore, even if consciousness were somehow a uniquely inexplicable phenomenon, it is a non sequitur that it must therefore be a bottom-up ontological primitive. This is not to mention that there is no clear “fundamental phenomenon” that can meaningfully be defined to constitute the simplest forms of “consciousness”. All senses can be muted or taken away; there is no obviously accessible or definable “bare awareness”. As Nagarjuna demonstrates in the Mūlamadhyamakakārikā (The Fundamental Wisdom of the Middle Way), all phenomena (dhammas) are empty of an intrinsic essence (sabhāva). If we cannot meaningfully describe nor define the conscious state of a rock or a computer, then what explanatory value is there in saying it is “conscious”? Interestingly, Kastrup differs here slightly: he argues that his analytical idealism is distinct from bottom-up panpsychism in that bounded consciousness is segmented from a larger, unitary consciousness. The problem here is immediately evident: again, what does he mean by “consciousness” here? The term is disastrously slippery. If he refers to that which everything is, then it is trivially true and completely useless.

Moreover, the mechanism by which this segmentation occurs is still irreducible: Kastrup, like other panpsychists and panpsychist-adjacents, produces no excess explanatory power, and only adds unnecessary metaphysical baggage. He writes: “nothing precludes the possibility that phenomenality takes place outside the field of self-reflection. In this case, we cannot report the phenomenality—not even to ourselves—because we do not know that we experience it.” In other words, Kastrup still proposes a mechanism outside of direct conscious experience that mediates consciousness, only he claims that this also constitutes “consciousness”: he has inflated the definition of consciousness without generating any extra pragmatic value. If, as open individualists posit, there is some “universal consciousness”, but we can neither access nor describe it in any useful manner, then is it really meaningful? What does it even mean for there to be a “universal consciousness” if we are in practice stuck in bounded subjectivity? Definitions are important here. It is easy to sound as if you are saying something profound through subtle linguistic manipulations, as I expose in Epistemic Telos.

Near-death experiences constitute one of Kastrup’s foundational arguments. He argues that a radically new metaphysics is justified because an increase in metabolism does not strictly correlate with an increase in the “richness of experience”: “under the physicalist assumption that experience is constituted or generated by brain activity, an increase in the richness of experience—as often entailed by self-transcendence—must be accompanied by an increase in the metabolism associated with the neural correlates of experience.” He notes that hypoxic near-death experiences often result in “richer” experience, and that psychedelics may generate more intense phenomena through inhibition rather than excitation. There are several glaring issues with this assertion. Firstly, “physicalism” is a language game: all that cannot be described by our current physical models are by definition extraphysical. This does not inherently justify a radical new metaphysics. In addition, “intensity” and “richness” are not commensurable phenomena, nor is the “amount” of “metabolism”. These are emergent gestalts that cannot reliably be reduced to unidimensional measurements between which precise mathematical relations can be drawn. Moreover, even those who argue that no significant extensions of the Standard Model are necessary to sufficiently account for consciousness have never suggested that the relationship between physical states and conscious experience must be so simplistic. Finally, there are just as many instances—if not more—where structural damage makes experience less intense: people with damage to the anterior cingulate cortex cannot suffer, damage to the optical nerve causes vision loss, and so on. Just because damage to the regions that control sensory gating can cause more subjective intensity, as in the case of Jill Bolte Taylor in My Stroke of Insight, does not mean we can therefore universalise an inverse correlation.

Edge of chaos

The universe started in an extremely ordered, low-entropy state. All was uniformly distributed, and there was thus zero distinguishability. Through an increase in entropy—the loss of structure, the progression of chaos—distinguishable structures emerged. We are currently living at what Norman Packard calls the edge of chaos: the point at which a significant increase in entropy would begin to reduce distinguishability. More structure does not entail more meaning. Just as linguistic ambiguity—through polysemy—allows for richer poetry, and spontaneous symmetry breaking allows for mass to emerge, up to a point, the loss of structure generates meaning, intensity, richness. Or note the existence of fork bombs, or Conway’s Game of Life: simple rulesets can generate incredibly intense outputs. Even the four-dimensional nature of spacetime is likely due to the fact that four-dimensional quaternions constitute the highest associative normed division algebra. The loss of commutativity beyond two-dimensional complex numbers is what allows meaningful progression of time to occur, but there is still just enough structure in the form of associativity to allow for complexity to persist. Again, spacetime sits at the algebraic edge of chaos. Contrary to Kastrup’s naive intuition, consciousness is far from unique in sometimes gaining intensity with a loss of structure. In The Master and His Emissary, Iain McGilchrist clarifies: “inhibition is, of course, not a straightforward concept. Inhibition at the neurophysiological level does not necessarily equate with inhibition at the functional level, any more than letting your foot off the brake pedal causes the car to halt: neural inhibition may set in train a sequence of activity, so that the net result is functionally permissive.”

Of course, this cannot go on forever. As entropy progresses, the entire universe will fade into indistinguishability. I expect protons to decay. We may see false vacuum decay. All complexity must end. All meaningful conscious experience sits at the edge of chaos. The brain is immeasurably complex. The body encapsulating the brain is even more so. The ecosystem that surrounds us, the Sun that sustains us, the laws of physics upon which life is contingent—all of these are highly complex, highly impermanent. We have never once observed a phenomenon that lasts; the immeasurable burden of proof is on those who claim it can be otherwise. Eternalist theories of time that suggest all points in time are equally “real” are also problematic: what does it mean for a point in time to be “real” if we cannot access it? How does this account for the asymmetric flow of time? We exist here, now, in a four-dimensional spacetime with mass and light and chemistry, because it is only at the edge of chaos that we could emerge. Even if you do not accept Wolfram’s maximalism in that all computational rules must exist, I find a Ruliad-adjacent metaphysics to be highly probable: a vast space of rules exist, and our universe does not sustain life by a freak accident; there were inevitably going to be rules that maintained just enough structure to sustain complexity, but not so little as to generate indistinguishable chaos. Everything we know tells us that consciousness is a metabolically expensive phenomenon that likely only evolved because it happened to be useful for the survival of certain, bizarrely complex creatures.

Immortality

As I explore in Epistemic Telos, we are evolutionarily predisposed towards generating preposterous theories of immortality. To support life, we may variously come up with the possibility of pleasant deaths to mitigate fear, validate life and promote reproduction; and unpleasant deaths to prevent suicide. Panpsychist-adjacent theories allow us to believe that our experience must never end. But it will. They also allow us to combat our existential loneliness with fantastical notions of “oneness” with the cosmos, as if love and the notion of mutual interdependence—what the Buddhists call pratītyasamutpāda—are not enough. In The Culture of Narcissism, Christopher Lasch writes:

The coexistence of advanced technology and primitive spirituality suggests that both are rooted in social conditions that make it increasingly difficult for people to accept the reality of sorrow, loss, aging, and death—to live with limits, in short. The anxieties peculiar to the modern world seem to have intensified old mechanisms of denial.

New Age spirituality, no less than technological utopianism, is rooted in primary narcissism. If the technological fantasy seeks to restore the infantile illusion of self-sufficiency, the New Age movement seeks to restore the illusion of symbiosis, a feeling of absolute oneness with the world. Instead of dreaming of the imposition of human will on the intractable world of matter, the New Age movement, which revives themes found in ancient Gnosticism, simply denies the reality of the material world. By treating matter essentially as an illusion, it removes every obstacle to the re-creation of a primary sense of wholeness and equilibrium—the return to Nirvana.

Lasch further appeals:

The best defenses against the terrors of existence are the homely comforts of love, work, and family life, which connect us to a world that is independent of our wishes yet responsive to our needs. It is through love and work, as Freud noted in a characteristically pungent remark, that we exchange crippling emotional conflict for ordinary unhappiness. Love and work enable each of us to explore a small corner of the world and to come to accept it on its own terms. But our society tends either to devalue small comforts or else to expect too much of them. Our standards of “creative, meaningful work” are too exalted to survive disappointment. Our ideal of “true romance” puts an impossible burden on personal relationships. We demand too much of life, too little of ourselves.

In general, there is no reason to suspect any consciousness is left once our bodies are destroyed. Once we die, the only patterns we have been able to detect that reliably correlate with consciousness disappear for good. Evidently, we cannot imagine a world in which we don’t exist, so many of us often tend to imagine some kind of primordial “blackness” or “stuckness”—but nonexistence is by definition the absence of experience. Even the experience of “stuckness” is a process that requires metabolic progression: if consciousness can be reduced to discrete, hermetic slices of time, there is no mechanism by which the continuity of awareness is generated. Theories of reincarnation or posthumous continuous identity are also equally absurd. They require some complex, transcendent mechanism by which our bounded consciousness is magically linked to another disjoint metabolic structure. We may survive anaesthesia, coma and concussion, but we have never survived brain death. Once the processes that sustain our consciousness cease, there can never be a return of subjectivity. Moreover, what happens when there are no longer any metabolic substrates to link to? In Images: My Life in Film, Ingmar Bergman writes:

My fear of death was to a great degree linked to my religious concepts. Later on, I underwent minor surgery. By mistake, I was given too much anaesthesia. I felt as if I had disappeared out of reality. Where did the hours go? They flashed by in a microsecond.

Suddenly I realized, that is how it is. That one could be transformed from being to non-being—it was hard to grasp. But for a person with a constant anxiety about death, now liberating. Yet at the same time it seems a bit sad. You say to yourself that it would have been fun to encounter new experiences once your soul had had a little rest and grown accustomed to being separated from your body. But I don’t think that is what happens to you. First you are, then you are not. This I find deeply satisfying. That which had formerly been so enigmatic and frightening, namely, what might exist beyond this world, does not exist. Everything is of this world. Everything exists and happens inside us, and we flow into and out of one another. It’s perfectly fine like that.

Attempts to explain the emergence of consciousness, in a way, are also a form of death denial. If we can understand it, perhaps we can control it! Theories such as integrated information theory (IIT) and functionalism, which often imply a weak form of panpsychism, routinely succumb to the confusion of language games. To start with IIT, if consciousness is equivalent to “integration”, how do we define “integration”? Why is consciousness equivalent to integration? How does consciousness arise from integration? Small changes in the choice of partitioning or other model parameters can yield wildly different calculated degrees of “integration”—how is this accounted for? Moreover, systems with random causal connectivity can have high degrees of “integration”—but digital logic gates are clearly not “conscious” in any sense that is meaningful to us. Or in the case of functionalism: if every mental state is to be defined in terms of a “functional role”, how are we to objectively define what a “function” is? By what transcendent mechanism does function become equivalent to mental state? Douglas Hofstadter’s strange loop theory of consciousness—the idea that consciousness arises from self-referential processing—is similarly problematic. As Žižek counters in Less Than Nothing:

Furthermore, when Hofstadter defines the Self not as a substantial thing, but as a higher-level pattern which can flow between a multitude of material instantiations, he is not consistent enough and repeats the mistake of the brain-in-the-vat fantasy: the “pattern” which forms my Self is not only the pattern of self-referential loops in my brain, but the much larger pattern of interactions between my brain-and-body and its entire material, institutional, and symbolic context. What makes me “my-Self” is the way I relate to the people, things, and processes around me—and this is what by definition would be lost if only my brain-pattern were transposed from my brain here on Earth to another brain on Mars: this other Self would definitely not be me, since it would be deprived of the complex social network which makes me my-Self.

Hofstadter’s alternative is: either my Self is somehow directly linked to a mysterious, unknown physical property of my brain and thus irreducibly rooted in it, or it is a higher-level formal pattern of self-relating loops which is not limited to my individuality but can be transposed into others. What Hofstadter lacks here is simply the notion of the I as the singular universality, the abstract-universal point of reference which, of course, is not to be identified with its material support (my brain) in a Searle-like way, but is also not just a pattern floating around and capable of being transposed into other individuals.

Models espoused by “qualia formalists” such as the Qualia Research Institute are little better—murky definition of “qualia” aside. They often take legitimately astute observations—such as some of Steven Lehar’s work on perceptual illusions—and autistically overgeneralise them to the point of meaninglessness. Take, for example, the entropic brain hypothesis by Robin L Carhart-Harris et al, which notes that certain psychedelically induced states correlate with a greater level of entropy in the brain specifically measured in a certain matter within certain networks, and therefore argues that “the quality of any conscious state depends on the system’s entropy”. This declaration is so preposterously vague that it can be made to say anything given an arbitrary definition of “quality” or “entropy”. Or take the “symmetry theory of valence”, which posits that the valence of any conscious experience—roughly, the quality of pleasantness or unpleasantness—depends on the symmetry of the mathematical object to which it is isomorphic. However, there is no indication that each “quale”—however it is defined—must adhere to some human-comprehensible mathematical formalism; and more pressingly, literally anything can be symmetric under a certain transformation. You just have to close one eye and squint hard enough. If multiple isomorphisms are present—some of which are not obviously symmetric under some arbitrary transformation, and some of which are—which formalism would be used?

Most theoretical frameworks of consciousness succumb to such definitional absurdities and vague overgeneralisations. Karl Friston’s free energy principle—which proposes that the brain attempts to reduce “surprise” or “uncertainty”—and predictive processing, which postulates that the brain is constantly updating a “mental model” of the environment in a “Bayesian fashion”—are just some of many confused language games that superficially appear scientific. Theories of consciousness such as these are often used to support the idea that we could one day transcend suffering through scientific “progress”, or even “upload” our consciousness into an immortal superintelligence. It is simply too much to bear for autistic metaphysicists—and I mean autistic descriptively in a non-clinical sense, not pejoratively—to accept that consciousness is incomprehensible, computationally irreducible, and finite. Most metaphysics is death anxiety.

Recurrence

Some physicists attempt to escape impermanence by positing theories of recurrence. The Poincaré recurrence theorem posits that certain dynamical systems will, after a sufficiently long but finite time, return to a state arbitrarily close to their initial state. However, this does not apply to our universe, because the state space demonstrably shrinks over time due to path dependence. Unlike idealised equilibrium thermodynamics, which assumes memoryless Markov processes, the diffusion of heat in non-equilibrium thermodynamics generates macro-scale history dependence. Other physicists point to the notion of ergodicity, the idea that a system will visit all possible states, to conclude that functional immortality as a conceivable state may eventually be inevitable. However, this is yet another confused language game: in a trivial sense, the universe does visit all possible states, since tautologically, all states that occur are the only ones that are possible. To clarify the definition, ergodicity is declared according to a certain set of combinatorial constraints that are coarse-grained by a particular observer—states that are imaginable under the Standard Model. Obviously, imaginability is not the same as strict possibility. For instance, consider an infinite sequence of digits: it is possible to imagine an equal distribution of every digit, but in practice, you may very well just see infinite zeros. As Sean Carroll remarks in The Universe Is Not Ergodic, in a classically ergodic universe, we would expect infinitely more random fluctuations than path-dependent ensembles, but we do not see Boltzmann brains—spontaneously formed, disembodied brains—or any other such oddities.

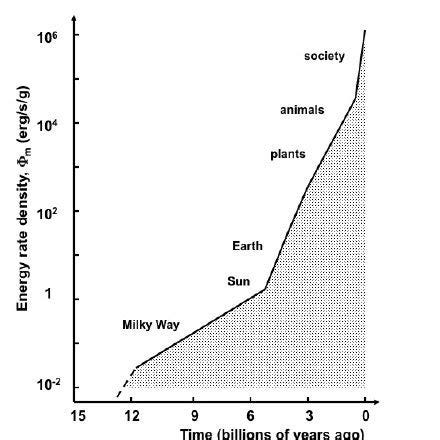

As entropy progresses, the existence of locally negentropic structures becomes exponentially less likely due to the overwhelming dominance of high-entropy configurations. Cyclic cosmological models such as the Big Bounce and conformal cyclic cosmology predict that the universe “iterates through infinite cycles”, but do not propose a cogent mechanism by which entropy magically resets. The variant of the Big Bounce in loop quantum cosmology, which is more parsimonious than other cosmological hypotheses, is not even necessarily cyclic. The Nietzschean idea of eternal recurrence is also half-baked: at what arbitrary point would the universe magically decide to revert to the initial state? When “maximum entropy” is reached? But there is no such thing as an absolute “maximum entropy”, so the universe would just have to decide by an undefined mechanism at some completely arbitrary point to remember the precise initial state. Hypotheses that local complexity can persist indefinitely are also delusional. In Cosmic Evolution, Eric Chaisson argues that complexity has risen drastically over time:

It should be immediately evident what is wrong with this graph. It specifically only measures the “energy rate density” locally on Earth—not to mention the arbitrariness of its definition in terms of energy over time per unit mass. Nuclear explosions also have a high “energy rate density”, orders of magnitude greater than anything on this graph. Arbitrary measures of energy flow do not tell us anything about how that energy is being used. In other words, energy rate density does not measure complexity; it tautologically measures energy rate density.

Coda

Everything was always going to end. Humanity was always going to go out in a brutal fashion; our future was never guaranteed. Death is a tragedy. Civilisational collapse is a tragedy. But I will also not pretend that I wanted civilisation to continue in the fashion that it has. In The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas, Ursula K Le Guin writes of the utopian city of Omelas, whose euphoric prosperity depends on the perpetual abject misery of a single child, locked in a cellar in filth and darkness. When residents venture to see the child for the first time:

They feel disgust, which they had thought themselves superior to. They feel anger, outrage, impotence, despite all the explanations. They would like to do something for the child. But there is nothing they can do. If the child were brought up into the sunlight out of that vile place, if it were cleaned and fed and comforted, that would be a good thing, indeed; but if it were done, in that day and hour all the prosperity and beauty and delight of Omelas would wither and be destroyed. Those are the terms. To exchange all the goodness and grace of every life in Omelas for that single, small improvement: to throw away the happiness of thousands for the chance of happiness of one: that would be to let guilt within the walls indeed.

She ends the story by describing the select few who decide to leave the city upon this discovery:

They leave Omelas, they walk ahead into the darkness, and they do not come back. The place they go towards is a place even less imaginable to most of us than the city of happiness. I cannot describe it at all. It is possible that it does not exist. But they seem to know where they are going, the ones who walk away from Omelas.

The question was never about how to prevent the end of humanity. Perhaps there was a time when it was about how to delay the end, but this appears increasingly unlikely as we run out of fossil fuels. I who walk away from Omelas know that the question was always about how to collapse with less suffering, less indignity. I would never suggest we accelerate the end. That is not up to any of us, not to mention the disastrous consequences that would result. But as sad as the end may be, we might also think of the void as a return to a sacred place where no wounds can open, where we might finally rest, where all the horrors of the world may ultimately heal. In Less Than Nothing, Žižek asks us to consider this perverse counterfactual:

One should thus (also) invert Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’s five stages of how we relate to the proximity of death in the Kierkegaardian sense of the “sickness unto death,” as the series of five attitudes towards the unbearable fact of immortality. One first denies it: “What immortality? After my death, I will just dissolve into dust!” Then, one explodes into anger: “What a terrible predicament I’m in! No way out!” One continues to bargain: “OK, but it is not me who is immortal, only the undead part of me, so one can live with it…” Then one falls into depression: “What can I do with myself when I am condemned to stay here forever?” Finally, one accepts the burden of immortality.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.