Controlled Chaos: Generative Rupture

Why moderate risk leads to growth and hormetic joy.

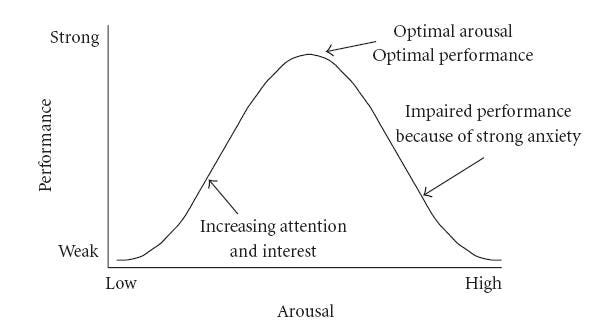

All meaning arises at the edge of chaos, that precarious liminality between order and disorder. Too much chaos is obviously catastrophic. But a world of perfect order is a dead world, homogeneous, timeless, empty. Attempts to maintain rigid structure always expend huge amounts of effort, accelerating surrounding chaos until it all collapses in on itself. Too much order is brittle, the way you grasp too tightly at something and end up crushing it. This is why heroin addicts self-destruct: money is spent, relationships are destroyed, and organs are damaged, until all the energy required to maintain that perfect high runs out, and the structure it depends upon collapses. If you ever subject yourself to the torture of reading medical journals, you’ll notice the inverted U-shaped curve show up a lot: too much or too little of a certain neurotransmitter or hormone deleteriously impedes function, whereas optimal performance is achieved somewhere near the middle. And you may have noticed that the most attractive people are endowed with an ideal blend of masculine and feminine traits, androgenic and oestrogenic, Apollonian and Dionysian. But really, this meta-pattern pops up everywhere: when naming his book The Name of the Rose, Umberto Eco chose the rose “because the rose is a symbolic figure so rich in meanings that by now it hardly has any meaning left”. A word with two or three discernible meanings allows for richer ambiguity than a word with only a single common definition. They call this ambiguity polysemy, and it is what makes poetry so vibrant. But a word that can mean anything is meaningless on net, pure symbolic entropy, which is why Baudrillard said we are drowning in meaning.

To survive, we need to maintain a certain level of order, but not so much that we turn static and brittle. This is why we evolved hormesis, also known as eustress in different circles: what doesn’t kill or severely maim us helps us to adapt to the endless flux of chaos. Take muscles, for example: it would be wasteful (and mildly carcinogenic) to just max out every muscle all the time. Instead, they can tolerate some damage in the form of microtears, which teaches them to grow stronger for next time. This is called antifragility. Muscles are sore for a bit before becoming more functional: a temporary burst of chaos settles back into a differently ordered state. This is also the mechanism behind the Dark Night of the Soul: major emotional development always requires a period of aimless depression and existential horror. Risk-taking is a signal that we’re exerting effort to improve our situation: this is why modern sedentary life feels so soul-crushing. The need to improve our capacity to withstand chaos is why novelty feels so good, and why we seek manageable thrills. Someone who isn’t adapting well and cannot let go of control will, in rough order of abjection:

try to simulate risk through travel, extreme sports, and BDSM (miserable, but still something to protect);

desperately seek salvation through reckless risk-taking and self-harm (miserable, and nothing to lose);

or fall into a risk-averse depression and avoid doing anything at all (miserable, and all hope lost).

As the world becomes more complex and we become more psychologically stunted, we lose our capacity to let go of control, and we seek refuge from the chaos through excess rigidity and safetyism. Relationships are scripted and filled with impossible expectations. Sex turns into contractual sadomasochism, where risk is simulated in a perfectly controlled and consensual fashion. Morality is turned into a sterile, transactional calculus. Obviously, this makes us miserable, and does nothing but accelerate chaos. When we believe long-term stability is impossible, we often gravitate towards hollow short-term domination, and our emotional circuitry is not adapted for modernity. Easy, milquetoast hits of novelty and fake risk screw with our dopamine regulation, causing our baseline to be more frustrating as we expect more stimulation by default. The only escape is to convince ourselves that the chaos isn’t totally life-threatening, that letting go of some control will not kill us. There is no magic formula for how much control to relinquish: that’s what our embodied cognition is for. Even if stuff feels bad in the short term, healthy intuition tells you whether something is nourishing or just destructive in the long run.

Rupture is the source of all intimacy. Laughter is the result of tension resolving into comfort: if I say something offensive or accidentally hurt myself, but then it turns out everything is okay, we laugh. Humour is surprise. Play is the controlled exploration of fear: we bond through giving others a chance to hurt us, and they show us that they can but won’t. All eroticism derives from this core mechanism: the capacity to annihilate or be annihilated generates the allure of power and vulnerability—Thanatos—and the refusal of this annihilation generates intimacy—Eros. Sadomasochism results when we cannot risk true emotional vulnerability, so we simulate it through controlled abuse. There is little genuine power or vulnerability, and thus even less intimacy results. And then of course, there is rape, paedophilia, and necrophilia, where we forgo intimacy entirely. These result when we keep seeking more and more extreme thrills to make up for our aversion to vulnerability and lack of intimacy. Andrea Dworkin said that all pornography leads to child pornography, and she wasn’t entirely wrong. We regain access to intimacy only when we let go of control. We restore healthy relation when we seek people who are similar enough to us that we can connect, but different and intractable enough that they can induce generative rupture. This terrifying unknowability—alterity, the transition from an it to a thou—is what keeps the spark alive, not some fantasy of completion or perfect agreement or total accessibility or transactional scorekeeping.

Our epistemic models work the same way. We can only seek truth through tolerating uncertainty, taking ridiculous shots in the dark. Each minor narrative rupture and broken fantasy opens up another raw wound of fear and uncertainty, a perpetual cycle of Dark Nights. They get subtler, but never become easy. It is only through restoring our capacity to withstand rupture that we can deal with the issues we face on a societal level.

As conceived in antiquity, erotic communication is anything but contented. According to [Marsilio] Ficino, love is the “most serious disease of all”; a “change,” it “takes away from a man that which is his own and changes him into the nature of another.” Such injury and transformation constitute its negativity. Today, through the increasing positivization and domestication of love, it is disappearing entirely. One stays the same and seeks only the confirmation of oneself in the Other.

— Byung-Chul Han, The Agony of Eros

For a denser elaboration on controlled rupture, see Epistemic Transgression. This essay was partially inspired by Venkatesh Rao’s treatise on differently free people, those who can routinely induce generative rupture; Henrik Karlsson’s exploration of Christopher Alexander’s unfolding, the continuous process of iterative rupture; and Karlsson’s musings on the pitfalls of boxing people into categories, an overinflation of the Imaginary preventing Real irruption. I should note that I make fun of Rao and Karlsson’s overly cerebral approach to this in my hilarious defence of embodied cognition, Anti-Agency. E T Janyes’ principle of maximum entropy is also the same idea: in a complex world, uncertainty is no longer always the threat we evolved to think it is, and it is more adaptive to minimise the set of assumptions and update priors in a pseudo-Bayesian fashion.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Also interesting: https://laymanpascal.substack.com/p/ordeal-ology-f77

oh, all of this.